The expense of 'just-in-time' gas imports over gas storage

A closer look at how the UK strategy favouring ‘just-in-time' gas imports over gas storage is proving expensive.

The start of the year has provided some vital insights into the local consequences in the UK of a perfect storm in the energy market. It has also highlighted structural weaknesses in the UK energy infrastructure. Simultaneous cold spells in Europe, in the Far East and elsewhere in the world have resulted in sky-high gas prices.

How was increased demand met during the last cold spell?

In the UK, the price of gas for delivery in the next month has increased from just 10 pence per therm (p/th) last summer to reach a high of 80 p/th on the 12th January. On that day, we saw the highest daily rise of the front-month contract for more than a decade.

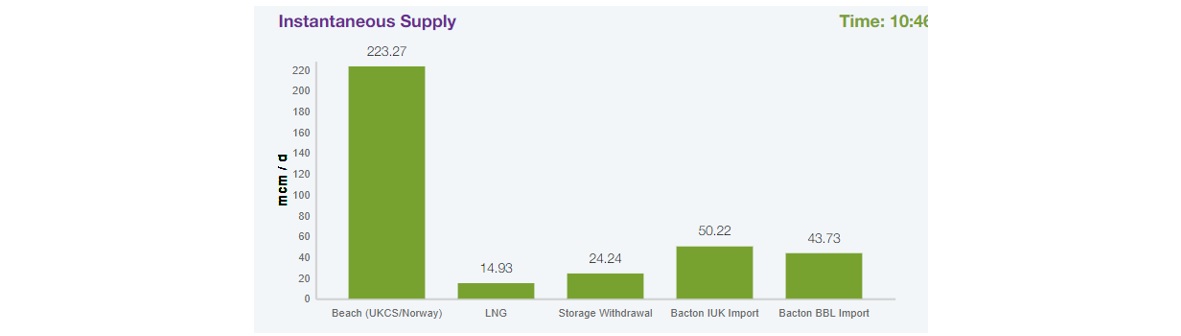

The following graph summarises the situation: local production and North Sea imports (Beach) were maximised. Large amounts of gas stored last spring in Europe during the Covid pandemic were delivered to the UK through continental interconnectors (Bacton IUK and BBL Import), responding to price signals. LNG deliveries remained stubbornly low. GB Storage was withdrawing at a quarter of the National Grid peak estimate for this winter in their Winter Outlook.

GB gas imports at 10:56 on the 13th January 2021. Source: National Grid

Why should we worry about the volatility required to attract expensive gas imports?

Volatility is a feature of energy markets, and the market is responding, we could argue. Prices in continental Europe in the rest of the World have also risen, so why should we bother?

-

Industrial and Commercial supply contracts tend to be indexed, or at least track month-ahead prices.

-

Domestic supply contract prices are likely to follow - watch out for the next update of the Ofgem retail price cap.

-

The wholesale UK gas market is showing a lower resilience than its European peers, with prices jumping to a premium of £4/MWh vs. the continent.

Of course, a large part of the gas being supplied this winter had been hedged by GB suppliers some time ago at much lower price levels (purchased in advance at a set price). Yet for the part of the demand that is bought closer to delivery, which corresponds broadly to the additional demand above the seasonal norms, the country’s importers must chase scarce gas and LNG on the world markets.

Assuming 100 mcm/day (or 1 TWh/d) additional imports over 30 days (this is what was booked on the interconnectors in early January to import continental gas), this £4/MWh premium payment over the TTF (European benchmark) price represents £120m extra paid by the UK consumer compared to the price paid on the continent, for just one month.

Japan demand gives support to spot LNG prices as JKM dislocates from other benchmarks

Gas Prices in Europe (TTF), USA (Henry Hub) and Far East (JKM). Source S&P Global Platts

To compare this with something we are all familiar with, consider the personal protective equipment (PPE) procurement race at the onset of the Covid crisis. The situation described in last November’s3 report of the National Audit Office (NAO) explains this perfectly: just replace “PPE” with “gas” and “Covid-19 pandemic” with “Beast from the East” and read again.

What makes the UK gas more expensive?

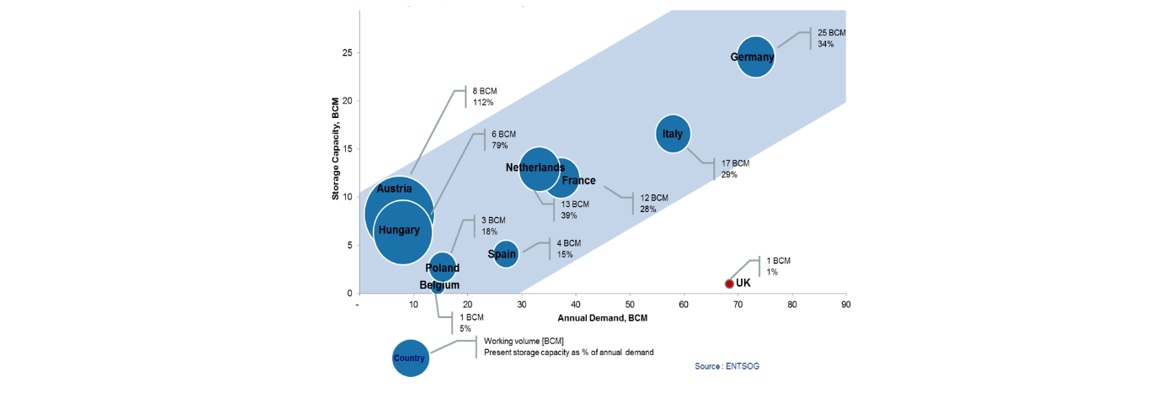

The UK stores under 2% of its annual gas demand on the British Isles vs. 25% on average stored in the EU27. This is the result of a decade of energy policies that have favoured ‘just in time’ gas import over the indigenous storage infrastructure. It is no wonder that we see gas flows currently being maximised on the pipeline linking the UK with the continent, but we can also see that attracting that gas to meet the demand is costing us dearly.

Storage Capacity in European countries vs annual gas demand. Source GIE, ENTSOG

As we are building back better with low carbon electricity sources, does gas still matter?

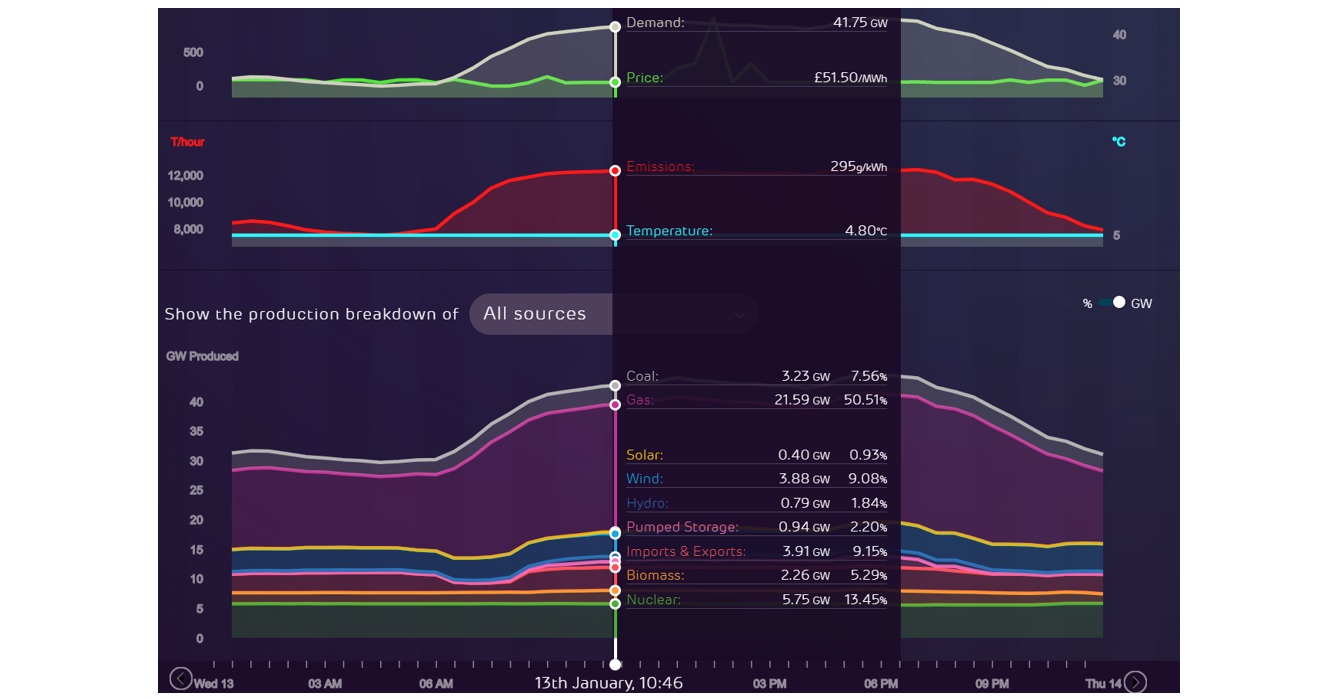

The vast majority of electricity used in the UK is already generated using gas. When the wind does not blow and the sun does not shine, we are left burning gas and coal to balance the electricity grid (and the communications of National Grid ESO on social media switches from how low carbon our electricity is to how tight system margins are) On the 13th January, gas was providing more than half of the electricity production, so it would not take much of a supply or demand shock for a sudden reduction in available gas to have a ripple effect on the electricity grid. If your solution to this is battery storage for electricity, consider that the entire battery storage of the country can deliver for just 1 or 2 hours less than fraction of a standard gas plant output, so they will not save the day.

GB Electricity Generation. Source: Drax Electric Insights

In the next few years, the withdrawal of coal capacity for electricity generation and the closure of the old nuclear power fleet will only exacerbate the UK’s reliance on gas-fired generation. It begs the question, how sustainable is the electrification of heat and of transport in that context?

A key structural weakness of the UK energy system lies in its tiny storage capacity.

The causes of the slow death of the GB gas storage sector are multiple. They are the logical consequences of being in a blind spot of the country’s energy policy. With revenues of storage assets under tremendous pressure since the 2008 financial crisis, punitive business rates levels combined with downward transition phasing mechanisms have compounded the issue. More recently, the Gas Charging Review has made GB storage even less competitive and the jury is out on how long the few remaining assets can remain in the market.

It is unknown whether this outcome was intended or not, but the consistency of the energy system’s reliance on gas, combined with absence of meaningful storage, does not look like the result of a well thought out energy policy.

The most recent UK Energy White Paper was published in 2007, prior to the financial crisis, at a time when Final Investment Decisions of energy infrastructure assets (including our Stublach gas storage site) were being taken. It is fair to say that the world has changed drastically since that era, yet the UK energy sector has been left in the dark without a clear direction.

The road ahead

As we build back better, the Government needs to commit to support green energy storage, and that is not only batteries. There are already viable infrastructure solutions to store bulk (TWh scale) green energy in gaseous form (biomethane and hydrogen), which should be encouraged.

The Government is wary of “picking winners” and willing to only commit funds to “no regret” projects. However, there is a real risk of delivering an inconsistent energy landscape that will replicate the current “non green” energy system and its flaws, namely the over-reliance on the kindness of strangers to balance the energy grids. That would cost the consumer and put reliability of energy supply at risk.

Many of these green infrastructure projects are located in the North of the country, building bulk storage is also a way to rebalance the economy and to offer well paid jobs.

Considering the points outlined in this piece, we are positive that a consistent energy policy for the UK energy industry would allow more energy companies to have the confidence they need to invest hundreds of millions on green energy projects, including bulk green storage of biomethane and hydrogen. This would ensure low carbon, competitive and reliable energy for UK plc and for the end consumer, as well as creating jobs in an industry that can then export its know-how globally.